Scientific Facts

| Common Name | Bog Turtle |

| Scientific Name | Glyptemys muhlenbergii |

| Life Span | More than 20 Years |

| Size | Average 3 to 4 inches. |

| Habitat | wooded areas |

| Country of Origin | Eastern United States |

What is a Bog Turtle?

The bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii ) is a gravely endangered species of semiaquatic turtle in the family Emydidae. The species is native to the eastern United States. It was first accurately reported in 1801 after the 18th-century study of Pennsylvania.

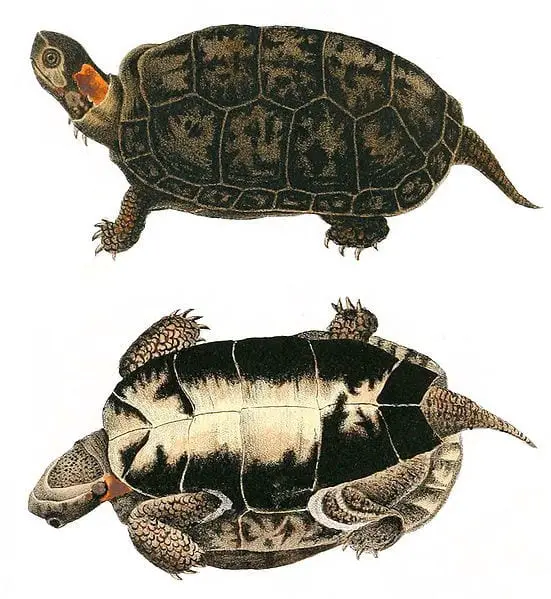

Appearance & Size

Tiny Bog Turtles are super adorable because they are so petite. They also have a somewhat lengthened scale. Young bog turtles will have a shell that is uneven in terms of its surface. However, that hardness will become more regular as the turtle grows older, particularly because these creatures like to excavate a lot.

You could modify a male Bog Turtle from a female by their extremities and carapace. A male will highlight a more solid and longer tail, as well as a slightly curved plastron. A female will have a level plastron and a scale that is broader and more arched in form.

It could be simple to recognize a Bog Turtle, gratitude to the brilliant red, yellow, or orange spot that is located on each surface of the animal’s head. The scale could occur anywhere from a brown shade to black, and each structural plate on the shell generally will highlight a light-colored core as well.

The framework will likewise be either brown or black, and it will stress some faded impression in an uneven design too. Lastly, the skin of the Bog Turtle will be brown or black, and it might also be spotted or striped with orange or red signings, especially on the sides of the scales on the limbs.

Geographical Range

Bog turtles are one of the most unusual turtles observed in the United States. Legislation forbidding the accumulation of the turtles for business has done few to cease the custom with bog turtles being a high-value species in several animal underground businesses.

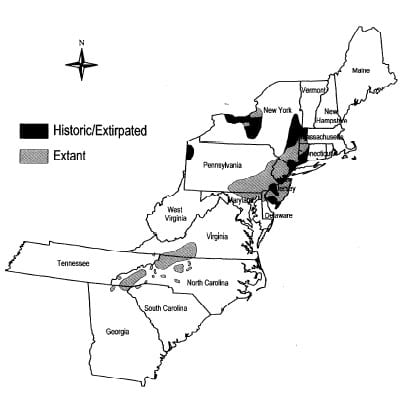

Bog turtle populations are separated into two separate populations distributed by a 250-mile distance. The northern populations located in New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey are registered as endangered. The southern populaces found in North Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, South Carolina, and Tennessee are registered as threatened due to correspondence of features.

Current bog turtle population is unexplored, but approximations reach from 2,500 to 10,000. Intrusive plants such as the purple loosestrife can shrivel out vast areas of adequate territory. Purple loosestrife spreads in large, dense clusters that are impermeable to the turtle, limiting its action.

Habitat

Bog Turtles commonly transpire in small, diverse populations, frequently invading open-shelter, herbaceous scrub fields, and swamps surrounded by forested areas. These wetlands are a collection of micro-habitats that involve bare holes, drenched areas, and states that are annually drowned. Bog Turtles depend upon this variety of micro-habitats for rummaging, lodging, lounging, sleeping, and housing.

Unfragmented riparian (stream) systems that are adequately powerful to enable the essential production of open territory are required to pay for environmental sequence. Beaver, fawns, and cows may be contributory in keeping the open-canopy wetlands necessary for this species’ continuity.

Bog Turtles occupy free, unspoiled result and hedge wetlands such as consecrate spring-bolster marshes, sphagnum bogs, bogs, swampy fields, and wet fields. These habitats are distinguished by soft, soggy grounds, sprinkled wet and dry hollows, vegetation managed by low weeds and shrubs, and a low amount of standing or gradual-moving water which frequently creates a system of shallow ponds and rivers.

Bog Turtles chooses spaces with adequate sunlight, high dissipation rates, high moisture in the near-ground microclimate, and permanent saturation of parts of the ground. Eggs are often placed in raised areas, such as the peaks of tussocks. Bog Turtles commonly withdraw into more massively vegetated areas to sleep from mid-September throughout mid-April.

The greatest menaces to the Bog Turtle are the damage, degeneration, and dissolution of its territory from wetland modification, construction, contamination, interfering species, and environmental vegetational continuation. The species is also tormented by accumulation for criminal wildlife business.

History of Bog Turtle

There have been only two reported findings of bog turtle remains. The deceased J. Alan Holman, a paleontologist, and herpetologist, first recognized bog turtle plaster remnant in Cumberland Cave, Maryland (near Corriganville), which are of Irvingtonian period (from 1.8 million to 300,000 years ago). The next breakthrough was of Rancholabrean (between 300,000 and 11,000 years ago) carapace parts in the Giant Cement Quarry in South Carolina (near Harleyville), by Bentley and Knight in 1998.

The bog turtle’s karyotype is comprised of 50 chromosomes. Subjects of modifications in mitochondrial DNA show low levels of hereditary mutation among bog turtle colonies. This is rare in species such as the bog turtle, which have uneven arrangements and are in small secluded groups (less than 50 people in bog turtle colonies). These circumstances restrict gene movement, typically heading to alteration between separated groups. Pieces of evidence denote that the bog turtle underwent a climactic decrease in numbers – a population bottleneck – as colonies were pushed south in front of coldness.

Declining icebergs pointed to the comparatively current post-Pleistocene development, as the bog turtles migrated back into their recent northern area. This current establishment from a comparably restrained southern population may consider for the decline of hereditary variety. The north and south populations are at present genetically confined, possibly as an outcome of cultivation and territory damage in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley throughout the American Civil War.

Diet & Feeding Habits

Bog turtles are omnivorous and consume water plants (such as duckweed), grains, drupes, worms, snails, slugs, bugs, other insects, frogs, and other little vertebrates. They also infrequently devour remains. Invertebrates such as insects are commonly the essential meal item.

In captivity, a bog turtle can be served a diversity of fruits and herbs, as well as meat such as liver, broiler hearts, and canned canine food. Bog turtles stuff solely during the day, but unusually during the warmest times, devouring their meals on the ground or in the water.

Common Behavior

The bog turtle is principally diurnal, productive throughout the day and hibernating at night. It rises in the early daybreak, relaxes until entirely hot, then launches its quest for food. It is an unsociable species, making it confronting to watch in its original territory. During colder days, the bog turtle will consume much of its time in thick bush, sunken, or concealed in the mud. Such response is suggestive of the bog turtle’s capacity to withstand without oxygen.

On milder days, the bog turtle’s movements include lurking, mating (throughout early spring), and relaxing in sunlight, the least of which it consumes a great opportunity of the day exploring. However, the bog turtle generally seeks refuge from the sun during the warmest part of the day. Occasionally, during moments of intense heat, the turtle will either slumber or become subterraneous, seldom invading channels of holes loaded with water. At nightfall, the bog turtle conceals itself in soft mines.

Late September to March or April is normally used in relaxation, either solitary or small groups in spring drains. These groups can include up to 12 kins and sometimes can incorporate other species of turtles. Bog turtles attempt to attain a region of thick soil, such as a healthy taproot system, for security during the latent phase. Though, they may sleep in other areas such as the underside of a tree, animal tunnels, or hollow areas in the mud. The bog turtle appears from slumber when the atmospheric temperature is within 16 and 31 °C.

The male bog turtle is proprietorial and will strike other males if they attempt inside 15 centimeters of his surroundings. An offensive male will slither toward an invader with his throat stretched. As he advances his opponent, he bends his shell by retracting his head and lifting his back legs. If the other male makes not withdraw, a battle of shoving and snapping can happen.

The fights normally persist merely a few minutes, with the bigger and more grown male normally prevailing. The female is also hostile when frightened. She will secure the area encompassing her nest, usually up to a range of 1.2 meters, from invading females, but when a young advances, she disregards it, and when a male emerges she capitulates her domain (excluding when mating season).

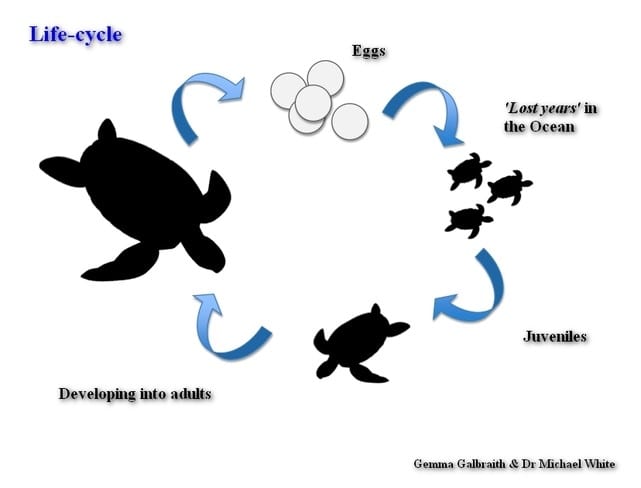

Reproduction & Life Cycle

The bog turtle has a profound reproduction scale; females produce one clutch per year, with a proportion of three eggs each. The juvenile manages to develop quickly, attaining genitive adulthood within the ages of 4 and 10 years. Bog turtles last for a standard of 20 to 30 years in the native. Since 1973, the Bronx Zoo has, fortunately, reproduced the bog turtle in custody.

Bog turtles are sexually developed when they enter within 8 and 11 years of life (both members). They breed in the spring after arising from slumber, in a mating concourse that normally persists for 5–20 minutes, generally during the midday, and may happen on ground or in the water. It commences when the male identifies the female’s genitalia.

During the dating routine, the male mildly snaps and bumps the female’s head. Younger males serve to be more proactive during mating, and females seldom seek to evade an extreme-aggressive male.

(male on right)

(male on right)

Nevertheless, as the female matures, she is more prone to take the fierceness of a male, and may also consider the position of an originator. If the female surrenders, she may retreat her front legs and head. After the whole process is completed, which usually gets nearly 35 minutes, male and female move separate directions. In a single period, females may copulate once, twice, or negative at all, and males strive to breed as many events as feasible. It has been recommended that the bog turtle can crossbreed with Clemmys guttata during the coupling season. Though, it has not done genetically documented in natural communities.

Lodging transpires between April and July. The female excavates a hole in a bare, sunny space of a marsh, and deposits her eggs in a green hummock or on sphagnum moss. The den is typically 3.8 to 5.1 centimeters under and 5 centimeters (2.0 in) around. Like most species of turtle, the bog turtle builds its nest utilizing its rear feet and claws.

Most bog turtle eggs are produced in June. Gravid females lay one to six eggs per clump, and breed one clutch per year. A strong female bog turtle can produce between 30 and 45 eggs in her existence, but many of the babies do not sustain to attain sexual adulthood. Typically, more grown females produce more eggs than younger ones. The eggs are white, oval, and on standard 3.4 centimeters long and 1.5 centimeters wide. Subsequent the eggs are yielded, they are abandoned to undertake a developmental period that serves for 42 to 80 days.

In cooler environments, the eggs are nurtured through the winter and arise in the spring. The eggs are helpless during the incubation phase and frequently slump victim to mammals and fowl. Also, eggs may be endangered by rain, snow, or several developmental dilemmas. It is unexplained how gender is identified in bog turtles.

Baby bog turtles are nearly 2.5 centimeters (0.98 in) long when they arise from their eggs, normally in late August or September. Females are somewhat tinier at origin and manage to develop more gradually than males. Both members grow quickly until they attain adulthood. Youngs roughly grow in stature in their initial four years but do not grow entirely matured until five or six years old.

The bog turtle consumes its time almost completely in the wetland where it produced. In its native habitat, it has a supreme lifespan of maybe 50 years or longer, and the standard lifespan is 20–30 years. The Bronx Zoo accommodates various turtles 35 years old or more, the most primitive identified bog turtles. The zoo’s compilation has triumphantly maintained itself for more than 35 years. The span of a bog turtle is defined by summing the number of loops in a scale, minus the initial one (which emerges before delivery).

How to Breed Bog Turtle

Mature bog turtles demand to be slept to coordinate their generative cycles. Hibernation methods differ, but some hobbyist chooses to relax their bog turtles individually and in shallow water at 6º C- 8º C for three to four months. The turtles must be starved and have a hollow digestive system before being calmed. This pre-hibernation fasting serves up to three weeks.

Once conscious, the male and female bogs turtles will stay insulated. You will set the male and females mutually, under surveillance, and depart them once there is flourishing copulation. The male will display vigorous snapping and bracing actions before venturing reception.

The female must obtain sufficient dietary calcium during the egg creation stage. Keepers supply calcium by creating a part of cuttlebone accessible to the female at all seasons.

The female will produce two to six eggs roughly six to eight weeks of subsequent arising from slumber. The nesting space must be administered a few weeks before her anticipated setting date. A suitable nesting area includes moist sphagnum moss, placed beneath the heat lamp, and surrounded by synthetic plants.

Once the eggs are placed, they are transported and then put into damp sphagnum moss.

Note: sphagnum moss is mostly preferred incubation setting due to its capacity to maintain dampness without removing it from the egg, and likewise for its essential anti-fungal properties. Sphagnum moss is not identical to forest moss.

The moss and eggs are held within a small pliable chamber vented with several small openings along the surfaces. The bog turtle displays hereditary sex drive; therefore, the incubation temperature doesn’t influence the sex of the developing embryos. The eggs can be nurtured within 25ºC and 28ºC (77F -83F). The incubation period ranges between 42-80 days and is controlled by incubation heats. There are various forms of incubators accessible, and any can operate, as long as the incubation setting stays humid during the whole incubation phase.

Recently hatched bog turtles are diminutive spanning 21-29mm in scale length. A baby may peek out its egg, create a cut merely big enough to push its head out and remain there for scant days before appearing entirely. The juniors must stay in the incubator and abandoned unscathed until they’re totally outside of their eggs, and their egg sac is consumed. Solely at this point can they be shifted to an adapted baby pen.

When a newborn bog turtle is observed for the prime time, it appears almost impracticable to think that this little turtle can withstand in the native. In captivity, newly hatched bog turtles are wary, and energetic and will flourish when held under excellent features.

Care Sheet

Housing

In terms of residence, the Bog Turtle could do great in a moderately straight cage. The answer is to give your pet with corresponding regions of shallow water and land so that you could imitate this breed’s native environment. A single Bog Turtle could do fine in a 3’ x 2’ tank, at least, while two turtles would need twice this amount of range. Also get it a point to install numerous hiding spots and sightline breaks throughout the cage as well, particularly if you possess more than one turtle.

Substrate

Select a soft foundation, such as nice compost or leaf rash, to incorporate the bare section of the enclosure. Shelters in the form of hollow woods, as an instance, are likewise essential, and they must be huge enough that your pet could comfortably spin around inside conveniently. And you could also supplement some shrubs in the dry area, as these could give more concealing spots for your pet.

For the marine section of your enclosure, you may not require any substrate. However, you should be equipped to provide your turtle passage to water that varies in measurement. Solely don’t get the water any vaster than the extent of your pet’s carapace. Adequate filtration and a method that enables you to replace the water regularly will also be essential to maintain the water clean and fresh.

Temperature

A basking area should hold a UVB lamp above it, and a radiator should secure the heat varies from 85-90°F. Atmospheric temperatures could be kept anywhere from 75-85°F, and water temperatures could be sustained at 65-75°F.

Applying heaters and automated clock, you could modify the amount of light that your turtle is vulnerable to throughout the year so that you could simulate the periods that the animal would be presented to in the native. Throughout summer, supply 16 hours of daylight, and then narrow that to 10 hours of light during wintertime.

Food & Nourishments

The Bog Turtle is an omnivore that relishes feasting upon a diversity of foods. These incorporate ants, dragonflies, beetles, and millipedes, as healthy as snails, spiders, slugs, and earthworms. These turtles could also devour rodents, frogs, nestling birds, and voles. And they won’t care to chew on bushes either, such as grains and berries.

To imitate its natural food, you could present your Bog Turtle with industrial pills for turtles, as well as pests like cockroaches and crickets. On top of that, you could supply your pet some sliced fish, marine plants, worms, green leafy herbs like grapes, romaine lettuce, strawberries, and melons.

Predators, parasites, and diseases

A host of various creatures, including snapping turtles, serpent species such as Thamnophis sirtalis and Nerodia siped, striped skunks, muskrats, reynards, raccoons, and canines prey against the bog turtle. Also, tapeworms and parasitic bugs disturb some individuals, creating blood loss and frailty. Their cases offer inadequate safeguard from predators. The bog turtle’s chief security, when frightened by an animal, is to immerse itself in soft mud. It seldom supports its area or munch when cornered.

Bog turtles may experience from bacterial diseases. Aeromonas and Pseudomonas are two genera of germs that induce pneumonia in individuals. Bacterial have also been observed in the lungs of two dead specimens found in 1982 and 1995 from colonies in the southerly community.

Availability

As with several species of an unusual animal, it is most beneficial to inquire at captive breeders when obtaining new specimens. Transporting any turtle from their native, particularly a species as endangered as the bog turtle, is not solely unlawful but likewise highly damaging to the surviving wild communities adhering weakly to viability. Furthermore, captive growers have the expertise and skill needed to assist you in giving sufficient administration for your new bog turtle.

Conservation and Threats

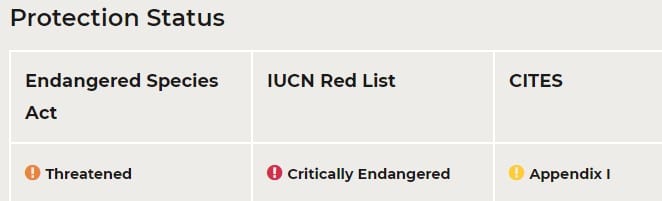

Preserved under the United States Federal Endangered Species Act, the bog turtle is deemed endangered in Delaware, Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts as of November 4, 1997.

Due to a resemblance of features to the northern population, the bog turtle is also endangered in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia (acknowledged to be the southern population). In addition to the general listing of endangered, nations in the southern area record the bog turtle as either threatened or endangered.

Alterations to the bog turtle’s territory have ended in the extinction of 80 percent of the populations that lived 30 years ago. Because of the turtle’s scarcity, it is also in a crisis of unauthorized accumulation, often for the comprehensive pet business. Despite laws preventing their accumulation, market, or exportation, bog turtles are generally held by bandits. Street transit has also pointed to deteriorations. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has a program for the restoration of the northern population. The bog turtle was classified as critically endangered in the 2011 IUCN Red List.

The intrusion of non-native shrubs into its environment is a huge menace to the bog turtles’ existence. Even though few plants intrude its ecosystem, the three principal offenders are reeds, reed canary grass, and purple loosestrife, which develop dense and towering and are considered to limit the action of the turtles. Such plants also out-challenge the endemic species in the bog turtle’s territory, thus decreasing the amount of meat and security accessible to the turtles.

The construction of new communities and pathways hinders the bog turtle’s transition between wetlands, thus hindering the endowment of further bog turtle colonies. Fly spray, drainage, and manufacturing detonation are all dangerous to the bog turtles’ environment and food stocks. The bog turtle has been appointed as a threatened species to “preserve the northern community of the bog turtle, which has severely decreased in the northeast United States.”

Now, the ricocheting of bog turtle communities relies on separate arbitration. Population regulating includes accurate land reviews over wide countries. In extension to studying land vividly, distant detecting has been applied to organically rank a wetland as either fit or inappropriate for a bog turtle settlement. This provides for correlations to be done between identified regions of bog turtle progress and possible areas of the prospective dwelling.

To support the current communities rebound, several individual designs have been launched in an endeavor to restrict the infringement of dominating trees and plants, the development of new roadways and communities, and other physical and man-made menaces.

Systems applied to reestablish the bog turtle’s habitat include: controlled burns to restrict the increase of commanding trees and forest (thus taking the environment back to old successional); feeding cattle such as calves and bucks in the sought environment area (building openings of water and freshly fermented mud); and supporting beaver venture, including barrier system in and around wetlands.

Confined breeding is another process of preserving the bog turtles’ quantities. The procedure involves coupling bog turtles indoors in constrained settings, where diet and partners are presented. Fred Wustholz and Richard J. Holub were the first to do this individually, during the 1960s and 1970s. They were engaged in teaching others concerning the bog turtle and in developing its community, and over a few years, they freed several vigorous bog turtles into the native. Several institutions, such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, have been authorized to reproduce bog turtles in custody.

What to Make if this Species Befalls on your Area or Project Location?

- Reach the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service early in preparing for any plan or project that may influence the Bog Turtle or its environment. Heed to New York Field Office Procedures for Project Reviews and Technical Assistance for guidance. Through the professional support or Project Reviews methods of the Endangered Species Act, the Service will give project-specific instructions to refrain or reduce unfavorable impacts to recorded species.

- Private landlords with an adequate environment can likewise communicate with the Service for site-specific, provident maintenance suggestions. Also, mechanical and tangible aid may be accessible through several State and or Federal plans to rebuild or persevere Bog Turtle territory. Most land in New York is personally owned. Willful preservation endeavors by New York’s citizens are crucial in the protection and restoration of vulnerable and endangered species.

FAQs

Why are bog turtles going extinct?

Due to population drops, limited territory preference, environment damage, and unauthorized accumulating, the bog turtle was classified as an endangered species in New Jersey in 1974

How many bog turtles are left in the world?

The south communities located in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia are classified as threatened due to resemblance of features. Latest bog turtle population is unexplained, but surveys vary from 2,500 to 10,000.

How many bog turtles are left in New Jersey?

The Department of Environmental Protection’s Endangered and Nongame Species Program calculates that there are several than 2,000 of these inmates of wetlands remain in the state

Are bog turtles endangered?

Critically Endangered

How can you describe if a wood turtle is male or female?

The most obvious approach to defining sex in a turtle is to study at the expansion of its tail. Female turtles have short and slender tails while males sport long, dense tails, with their vent placed closer to the edge of the tail when matched to a female

Can turtles live up to 500 years?

For instance, a common pet turtle can last between 10-80 years or so, while more massive species can comfortably be over 100 years. It is tricky to estimate the period since it needs centuries, some speculate that a few turtles could hold approximately 400 to 500 years old.