A lot of researchers, hobbyists, and breeders want to know the exact gender of their pets. There are times when it is easy to do, especially for the sexually dimorphic animals. You can determine their sex by just looking at their physical features.

However, in other animals and juveniles, determining the sex may not be so straightforward. It is impossible despite its importance. Determining the gender of a developing lizard is sometimes done by using tissue samples or the embryo itself.

The gender-determining mechanisms in reptiles are strangely diverse. They range from the systems which are under comprehensive genetic control to those which are extremely dependent on the temperatures which the embryo experiences throughout the development process.

While the reptiles are exhibiting a remarkable and diverse range of sex identification techniques, lizards tend to be responsive to the sexing and testing methods involving their DNA.

Overview

Determining the sex of a lizard through DNA seems to be the most practical choice. At times, it appears to be the only possible option. DNA testing has been used for most avian species for more than 15 years. It involves collecting a small drop of blood that will be subjected to DNA assessment.

Unfortunately, this new technology seems to be a big challenge when used in lizards because the DNA parts of the chromosomes that are responsible for sex identification are difficult to recognize.

To determine the DNA sequencing in lizards, one will require a kind of funding or grant to examine the genes and chromosomes to recognize the parts associated with sex identification. So far, the only lizards that can be sexed using DNA analysis are the Komodo dragon and green iguana.

DNA sexing for lizards is not commercially available yet. Until it becomes commercially available, researchers will have to depend on some other techniques of sexing lizards. For instance, most chameleons come with secondary sexual characteristics, which may help distinguish females from males.

Most lizards have 2 bulges at the back of their cloaca. Others have enlarged pores that can be seen beside their cloaca or on their ventral femur.

The adult male bearded dragon has a protruding dark beard. Some species can be explored to identify the sex through examining the depth from which the probe would go once introduced caudally in the cloaca.

Most reptile textbooks define the available methods to use in identifying the gender of various species. You may also talk to experienced herpers and get some tips from them on how to determine the gender of your pet lizard.

If you have to collect a blood sample from the lizard for some other purposes, look for those textbooks that show the proper way to do venipuncture. In most herps, there’s a tail vein that you can use for collecting a blood sample. In big snakes, the vein within the oropharynx called palatine vein can be used. A cardiac puncture will also be a good option. For some frogs, toads, and lizards, they have a big accessible vein running along their ventral abdomen in the midline.

If you are a novice lizard keeper, then you should join herp continuing education programs and work with the affiliated wet laboratories that can provide you hands-on experience in carrying out basic procedures and collecting blood on more common lizards.

Challenges Associated with Determining Sex of Lizards and other Reptiles

Unlike the birds and mammals, reptiles like lizards were believed to have evolutionary unbalanced sex determination systems. Due to that, scientists will struggle to come up with an effective and widely available tactic for studying and exploring it. There are several ways to determine the sex of reptiles like lizards. These methods range from the well-distinguished sex chromosomes to temperature-dependent gender recognition systems.

In those species to which the temperature-dependent gender determination systems are applicable, the gender of an animal is set by the incubation temperature. There are no differences found in the males’ and females’ genotypes. Therefore, for these animals, it is impossible to distinguish sex through DNA.

In the temperature-dependent sex identification, it’s the environmental temperature throughout the embryonic development’s critical period determines whether the developing individual will become a male or a female.

This particular period takes place after the mother laid the eggs. Therefore, sex identification in reptiles depends on the ambient conditions that affect the clutches of eggs in the nests. For instance, in most turtle species, the eggs from the cooler nests will be males, while those on the warmer side of the nests will be females.

In other reptiles like the American alligators, both high and low temperatures lead to the development of females, and intermediate temperatures encourage the unborn babies to be males. A widely held view will be that the genotypic and temperature-reliant sex identification is equally exclusive and incompatible mechanisms. Therefore, the sex of a reptile is not control of the environmental temperature and sex chromosomes.

There’s no genetic predisposition for the temperature-sensitive embryo to develop and become male or female. Hence, the early embryo doesn’t have a specific gender until it goes into the thermosensitive phase of embryonic development.

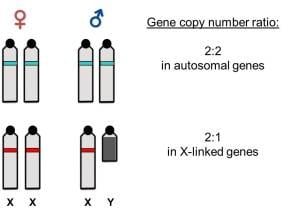

Most reptile lineages come with genotypic sex identification that depends on the existence of ZZ/ZW or XX/XY sex chromosomes. Those lizards with ZW or XX sex chromosomes are females, while those with ZZ or XY are males. Molecular sexing will be a choice for these individuals.

The past techniques for molecular sexing in lizards depend on the identification of the sex-specific variances in the repetitive series in genomes. These are dynamic and will demonstrate the intra- and interspecific variation.

That means those methods cannot guarantee precise sex identification in lizards. The August 2017 edition of the Methods in Ecology and Evolution revealed that the scenario in lizards is not as difficult as it seems, and it is somewhat realistic to think that researchers can determine the gender of species through molecular sexing in approximately 4,000 snake and lizard species.

Sex identification is not extremely unstable in lizards as compared to birds and mammals. The sex chromosomes appear to be conserved in multiple lineages of snakes and lizards. Therefore, the protein-coding genes found on the sex chromosomes of these animals can help and be used as accurate markers for gender identification.

Molecular Sexing

The well-differentiated sex chromosomes vary in the gene content. The differentiated unpaired W and Y chromosomes have degenerated. They also lack most of the genes that still exist in their Z and X counterparts. Meaning, in the lineages that have distinguished sex chromosomes, females previously have a distinct total count of copies of genes related to their sex chromosomes as compared to males. The measured differences in the total count of copies of Z- or X- linked genes in the DNA sample gathered through qPCR or quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction can be suitable for molecular sexing. In applying this method, one should know some Z- or X- linked genes in the provided lineage. This will not be as simple as the sex chromosomes evolving among the reptiles for many times; W and Y chromosomes should have tolerably degenerated. It will work just in the lineage in which the species are keeping similar sex chromosomes. When it comes to any other techniques used in molecular sexing, the tests in different species with identified sex is suggested for the old, unstudied animals.

Where and How does the Molecular Sexing Base on qPCR Work?

Experts have designed several primers for the gender-associated genes that they used as molecular sexing indicators. These primers were all tested in more than 90 reptile species. The molecular sexing technique that is based on the qPCR is accurate in the lacertid lizards with ZW/ZZ chromosomes, advanced snakes with ZW/ZZ chromosomes, and iguanas with XY/XX chromosomes. Those lineages enormously conserved the sex chromosomes and involve about 4,000 species that are okay with molecular sexing.

In the past few years, a similar technique was made for the softshell turtles. Since most of these turtles are already endangered and sexing, the juveniles have been so difficult for the previous several years following the hatching time.

Molecular sexing can be advantageous for both breeding and conservation projects designed for various species, including lizards. Researchers are expecting that the molecular sexing technique is soon to be available for other lizard lineages in the next few years. Researchers are now working on various reptile lineages to know more about their sex chromosomes and create primers for the sex-linked genes applicable to the qPCR-based version of the molecular sexing technique.

Conclusion

While researchers don’t see progress in using molecular sexing and DNA sex identification in lizards, still there is always hope for discoveries in the next few years. As the technology is continuously advancing, the chances are that molecular sexing in lizards will become more available and easier to use in determining the gender of every newborn. For now, it has been proven helpful and effective though getting accurate results is not always as easy as how these techniques work for other reptiles.